Chapter 9: Rethinking Access to Justice and Pro Bono

Chapter Overview

In Chapter 8, we explored how existing ethical and regulatory frameworks apply to lawyers’ use of generative AI, highlighting the duties of competence, confidentiality, candor, and supervision in this evolving landscape. We examined new court orders requiring AI disclosure, bar opinions emphasizing the need to verify AI-generated work, and real-world disciplinary cases that underscore the high stakes of failing to meet professional obligations. We also addressed the risk of bias in AI systems and how flawed training data or assumptions can lead to unjust outcomes. Overall, the chapter underscored that technology may change legal tools, but it does not alter a lawyer’s core responsibilities.

In this chapter, we examine one of the legal profession’s most important yet longstanding challenges: bridging the gap between people’s legal needs and the resources available to help them, often referred to as the “justice gap.” We explore the realities of access to justice (A2J) in the United States, highlighting how insufficient funding, heavy caseloads, and complex procedures can leave millions without the legal help they need. We then examine how generative AI, a type of artificial intelligence that can generate text and other content, offers new tools to transform access to justice, from legal chatbots that guide litigants through court forms to AI-powered research systems that assist pro bono attorneys.

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Identify key challenges in traditional access to justice and pro bono models, including funding constraints, legal complexity, and gaps in representation.

- Analyze how generative AI tools (e.g., legal chatbots, document automation, AI-assisted legal research) are transforming the delivery of legal aid and pro bono services.

- Compare AI-powered legal assistance models with traditional pro bono approaches, evaluating efficiency, scalability, and equity outcomes.

- Apply AI-driven tools to real-world legal aid scenarios, illustrating how automation can streamline intake, case management, and client interactions.

Let's begin with understanding what is access to justice, the justice gap and how generative AI may help.

Defining “Access to Justice” (A2J)

“Access to justice” means ensuring that people can obtain fair, effective assistance for legal matters, whether through a lawyer, legal aid services, or user-friendly court processes. In criminal cases, we often refer to the constitutional right to counsel for defendants who cannot afford an attorney. In civil cases, there is no universal right to a free lawyer, and navigating the legal system can be daunting for those without resources. When people talk about the “justice gap,” they usually describe the mismatch between the legal needs of low- and middle-income individuals and families, and the limited resources available to help them.

Why the Justice Gap Matters

- Fairness: If someone cannot find or afford a lawyer, they might lose a home, child custody, or critical benefits simply because they do not understand the law or legal procedures.

- Court Efficiency: High numbers of unrepresented litigants can slow down court dockets and overwhelm judges and clerks who must explain procedures to people who have no legal background.

- Social Impact: Lack of legal representation often exacerbates other problems, such as homelessness, debt cycles, and family instability.

Key Term

Justice Gap: The mismatch between the number of people needing legal help and the resources available to provide it, often resulting in individuals going unrepresented or not receiving any meaningful assistance for critical legal issues.

How Generative AI Fits In

Generative AI tools are emerging that can automate routine tasks like drafting documents, summarizing cases, and answering frequently asked questions. If used ethically, these tools can help legal aid organizations, pro bono lawyers, and court systems reach more people and offer faster, more affordable services.

The Current State of Access to Justice in the United States (2021–2023)

To understand how AI might help, it is essential to grasp the challenges that make access to justice so difficult in America. Recent studies and other data paint a clear picture of systemic underfunding, overwhelming caseloads, and emerging issues following the COVID-19 pandemic.

Overview of the U.S. “Justice Gap”

Over the past three years, multiple studies and reports have indicated that millions of people in the United States continue to be left behind when it comes to legal representation. Many of those at the lowest income levels find themselves shut out of an increasingly complex court system, a problem exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and by structural underfunding of legal aid programs.

A recent Legal Services Corporation (LSC) study revealed two alarming statistics:

- 74% of low-income households faced at least one civil legal problem during the study year

- 92% of these substantial legal problems received no or inadequate legal assistance

The severity of these statistics cannot be overstated, as they represent hundreds of thousands of Americans being forced to navigate the civil justice system without meaningful help or guidance. The root cause often lies in the cost of professional legal services, something unaffordable for many families who are living paycheck to paycheck or experiencing sudden financial hardships such as job loss. These problems range from housing disputes to family law crises, creating a justice gap that continues to widen for America's most vulnerable populations.

Legal Aid Availability and Funding

Civil legal aid, typically delivered by nonprofit organizations funded in part by the LSC, remains the only recourse for many low-income individuals dealing with issues like eviction, domestic violence, or consumer debt. Yet the demand for this help far exceeds the supply.

- In 2024, the LSC documented that its partner organizations had to turn away roughly half of eligible cases simply because there were not enough attorneys or staff to go around

Although the federal budget appropriation for LSC rose from about 489 million dollars in 2022 to around 560 million in 2023, the organization had requested over one billion dollars for 2022 alone to address what it deemed "pandemic-related surges" in housing, unemployment benefits, and debt collection cases. Legal aid providers continued to handle more than 1.9 million yearly requests for help but could fully resolve only about half of them. In effect, thousands of low-income people were left to fend for themselves despite being income-eligible for assistance.

Public Defender High Caseloads and Alarming Consequences

Problems in criminal defense have proven daunting. The constitutional right to counsel for indigent defendants has, in theory, established a bedrock principle of fairness, but in practical terms, many public defender offices remain under-resourced and overloaded. Guidelines dating back to 1973 suggested that a single attorney could handle up to 150 felonies or 400 misdemeanors per year.

- One national study released in this year found that public defenders routinely carried workloads that were double or triple the modern recommended thresholds, leading one expert to describe the state of criminal defense in some places as "legal triage."

In Oregon, a 2022 shortage of public defenders left over 700 defendants without representation, ultimately prompting courts to dismiss close to 300 cases, including some felony matters. The fact that a serious charge could end up dismissed not because of the case's merits, but due to systemic under-resourcing, calls into question the very integrity of the justice system.

Example Scenario

Public Defender’s Office With AI-Enhanced Discovery

A public defender’s office receives gigabytes of digital discovery, body cam footage, text messages, social media logs, for a high-stakes felony case. Manually reviewing all this data would take weeks. The office implements an AI platform that highlights suspicious or exculpatory evidence. Lawyers confirm the flagged evidence, cutting review time by 60%.

Reflection Question: What ethical safeguards must be in place to ensure the AI’s recommendations do not overlook critical data or compromise client confidentiality?

COVID and Court Accessibility

COVID-19 forced courts to shut down or limit in-person hearings. Jury trials were often delayed, creating a mounting backlog in both civil and criminal cases. Virtual hearings, which had been rare before 2020, became widespread. Remote proceedings improved attendance rates because parties no longer needed to travel to courthouses or arrange for childcare, and this shift seemed to expand access for segments of the population.

- According to a report by the National Center for State Courts, some remote hearings took over a third longer than in-person sessions simply because participants had trouble connecting.

However, the transition to Zoom and similar platforms also revealed a stark digital divide. Many unrepresented litigants lacked broadband internet, appropriate devices, or the technical know-how to navigate online hearings. This meant that while remote technology opened doors for certain groups, it also forced some people out of the system due to technological barriers, thereby reinforcing existing inequalities.

Civil Justice Issues: Eviction, Consumer Debt, and Family Law

Within the broader civil justice realm, eviction and consumer debt cases continue to be illustrative of how representation inequities translate into real-world consequences. Even before the pandemic:

- More than 70% of defendants in debt collection lawsuits did not have legal counsel

- Landlords usually enjoyed representation rates upwards of 80%

Studies have shown that tenants who appear in court with counsel are far more likely to avoid the immediate threat of homelessness and can often secure better agreements with landlords.

Meanwhile, debt collection suits, already one of the fastest-growing categories of civil litigation, continued to surge as pandemic-related financial strains drove more individuals into delinquency on rent, credit cards, or medical bills. Family courts also exhibited deep cracks in access to justice. People seeking divorces, child custody determinations, or protection orders routinely proceeded pro se.

- In some states, estimates showed that up to 80% or 90% of family cases had at least one self-represented litigant

During the pandemic, domestic violence cases added new layers of complexity when remote hearings made it difficult to present evidence or ensure safe communication for survivors seeking protective orders. At the same time, court cutbacks and social distancing delayed hearings, creating backlogs and leaving families in limbo over custody arrangements and support orders.

Example Scenario

Tenant Facing Eviction

Sarah, a single mother, receives a five-day eviction notice. She cannot afford a private attorney. Under traditional pro bono, she might spend days calling volunteer hotlines, hoping to find a free lawyer. Under traditional legal aid, she faces a waitlist because of staff shortages. Under an AI-powered model, Sarah uses a website chatbot at midnight, inputs her case details, and gets a draft defense form to file with the court the next morning.

Reflection Question: How do efficiency, cost, and availability differ among these three approaches?

Disparities by Income, Race, and Geography

Racial and socioeconomic disparities have also played a critical role in shaping the current state of access to justice. Eviction data revealed that Black and Latino renters, especially women, encountered disproportionate rates of displacement in many urban areas, and language barriers continued to pose challenges for non-English speakers. In rural “legal deserts,” people of all races faced the logistical hurdle of living in counties with few or no attorneys, which forced them to drive long distances for legal aid or rely on underfunded volunteer programs that might only visit occasionally.

Key Challenges in Traditional Access to Justice and Pro Bono

Many people depend on pro bono attorneys or volunteer-based legal services to fill gaps in representation. However, the traditional pro bono model also faces obstacles.

Funding and Volunteer Constraints

Chronic underfunding of both civil and criminal legal services forces organizations to ration aid, despite modest increases in federal appropriations in recent years. LSC leadership has repeatedly testified that billions, not millions, are needed to adequately serve low-income populations, leading legal aid offices to make difficult case prioritization decisions. While pro bono work provides valuable support, it relies on limited volunteer hours and donations, making it insufficient to address the massive gap in legal resources that leaves many eligible clients without representation.

Legal Complexity and High Caseloads

Public defenders and legal aid lawyers struggle with overwhelming caseloads that prevent thorough investigation of each client's situation, while simultaneously navigating increasingly complex legal procedures in areas like eviction, consumer credit, and family law. Court forms intended to help self-represented individuals often contain confusing legal jargon, creating additional barriers. Criminal defense faces similar challenges, with outdated caseload standards and complex discovery requirements increasing the risk of oversight and rushed plea deals. Despite judges' potential desire to ensure thorough representation, pressure to clear crowded dockets frequently forces rapid case processing at the expense of careful consideration.

Representation Gaps and Unfair Outcomes

Millions of Americans with critical legal needs, such as eviction defense or domestic violence protection, proceed without a lawyer. This drastically decreases their likelihood of a fair result. A landlord may arrive to eviction court backed by an attorney who knows the rules, while a tenant comes alone without any sense of how to file a written response or how to argue that the eviction notice was defective.

- A 2020 study by the Pew Charitable Trusts, focusing on debt collection lawsuits, estimated that more than 70% of such cases ended in default judgments

This imbalance in legal skill sets virtually guarantees that tenants lose their homes at higher rates, and it has a ripple effect throughout the broader community, from increased homelessness to strained social services. The high rate of default judgments occurs primarily because defendants never responded or did not appear in court. That outcome might have been different if they had understood how to file a basic answer or had access to an attorney to negotiate on their behalf.

Geographic Hurdles and Underserved Regions

Geographic inequities present yet another stumbling block. In urban settings, legal aid offices often exist but are swamped by the sheer volume of requests. In contrast, rural areas in states such as Montana or large portions of the South might have only a handful of lawyers covering vast geographic regions. The American Bar Association has documented these “legal deserts,” noting that around 1,300 U.S. counties have fewer than one attorney per thousand residents.

Key Term

Legal Desert: A region (often rural) with extremely few or no practicing attorneys. Residents in these areas may have to travel long distances or rely on intermittent volunteer clinics to receive any legal assistance.

Pandemic-Exacerbated Shortfalls

The pandemic compounded many of these existing challenges in ways that even the most committed legal advocates could not have predicted. While organizations pivoted to remote service delivery to maintain some level of operation, many offices lost staff or had to scale back in-person clinics that historically drew volunteer attorneys to do pro bono work. With everyone juggling new responsibilities, from child care to caring for sick family members, the pro bono pool itself was strained. Virtual volunteer models emerged, but online training and supervision required for new attorneys unfamiliar with legal aid processes added to the workload of already overstretched staff attorneys, sometimes limiting how effectively that extra help could be deployed.

Potential for Bridging the Justice Gap with Generative AI

While large law firms have invested in AI-assisted document review and contract analysis for years, legal aid organizations, public defender offices, and pro bono programs have often lacked the resources or expertise to do the same. According to a January 2025 field study:

- 90% of legal aid attorneys who tried generative AI found that it reduced their administrative workloads

- 75% planned to continue using these tools

Encouraged by such numbers, more nonprofits and court systems are looking to generative AI as a potentially transformative way to scale their assistance to underserved communities. Researchers and advocacy groups nonetheless stress that generative AI is not a panacea. As the technology is relatively new in the legal sector, it must be carefully monitored for inaccuracies (“hallucinations”), bias in training data, and the risk of security breaches when sensitive client information is uploaded.

In most accounts of how AI can help underserved populations, three themes emerge consistently: AI’s capacity to automate repetitive tasks, its ability to operate at scale, and the promise that these technologies can make legal help more affordable. Taken together, these elements could help alleviate the chronic underfunding and staff shortages that have plagued legal aid offices and public defender agencies for decades.

Automation of Repetitive Tasks

One of the clearest benefits of generative AI for lawyers, particularly those working in nonprofit settings with heavy caseloads, is its power to handle routine work that might otherwise swallow up hours of attorney or paralegal time. For example, automating routine, time-consuming tasks like client intake, form-filling, meeting note summarization, letter drafting, and document analysis.

A San Bernardino, California pilot program demonstrated these tools' transformative potential: after implementing AI-assisted intake and pleading drafting systems, a legal aid agency more than tripled its eviction case capacity from 2,500 to over 8,000 clients annually while reducing staff burnout. Similarly, an innocence project team reported saving hundreds of hours on post-conviction case reviews through AI-powered document analysis, enabling faster screening of wrongful conviction claims and expanding their capacity to serve justice-involved individuals.

Scalability

Scalability is another key advantage often attributed to generative AI in legal contexts: unlike human staff limited to serving one client at a time, AI chatbots and intake systems can simultaneously handle thousands of requests 24/7. This capability is particularly valuable for nonprofits that routinely turn away eligible clients due to resource constraints.

In 2025, Nevada's judiciary demonstrated this potential by launching an online self-help portal with an AI chatbot supporting over fifty languages. Within months, thousands of users had interacted with the system, often outside normal business hours, and obtained customized forms for small claims and family law matters. A significant achievement in a rural state where geographic distance from legal aid offices creates substantial access barriers.

Affordability

Affordability is a crucial advantage of AI-assisted legal services, particularly for organizations operating on limited grants, government funding, and donations. While increasing attorney headcount creates ongoing salary and benefit costs, AI solutions may be funded through one-time philanthropic grants or software license purchases. Some law firms contribute their in-house AI resources or offer cost-sharing arrangements as part of corporate social responsibility initiatives.

The affordability benefit extends to individual clients as well: when routine document preparation and screening processes are automated, lawyers can significantly reduce their final bills, making "low bono" services accessible to those who earn just above legal aid eligibility thresholds but cannot afford standard legal fees. For qualifying low-income clients, AI-driven efficiencies allow legal aid offices to maximize limited budgets, serve larger client populations, and address more complex legal matters without requiring additional funding.

In all these ways, automating basic tasks, scaling outreach, and cutting the costs of service delivery, generative AI holds the potential to chip away at the justice gap.

Generative AI Use Cases to Address the Justice Gap

1. Document Analysis and Summarization

Legal aid attorneys often deal with massive amounts of paperwork (e.g., trial transcripts, discovery documents, or government records). AI-driven tools can scan these documents, highlight key details, and produce quick summaries. This allows lawyers to spend less time sifting through data and more time building a strong case or counseling clients.

Example: An Innocence Project team used an AI assistant to review hundreds of pages of witness statements, identifying inconsistencies that supported a post-conviction relief motion.

2. Drafting and Research Assistance

Generative AI can create first drafts of pleadings, motions, or letters. Lawyers then revise and finalize these drafts, ensuring accuracy. Similarly, AI systems can quickly comb through legal databases to find relevant statutes and cases, dramatically cutting down on research time.

Example: A pro bono attorney might use an AI tool to draft an eviction defense motion. The attorney then carefully edits the document, verifying citations and legal arguments before filing.

3. Client Intake and Guidance

Chatbots can guide individuals through initial intake questionnaires, gather facts about their problems, and direct them to relevant forms or resources. This streamlines onboarding for legal aid offices.

Example: In San Bernardino, an AI-powered intake process helped quadruple the number of clients served by automatically collecting key facts, generating draft documents, and scheduling consultations.

4. Language Translation and Plain-Language Explanations

Legal jargon and English-only forms are a major barrier. AI translators and “plain-language” generators can convert official documents into understandable text for clients with limited English proficiency or low legal literacy.

Practice Pointer:

If your client speaks limited English, use AI translation software to provide initial explanations and documents in their native language, then confirm accuracy with a bilingual staff member or translator.

5. Administrative and Non-Legal Tasks

AI helps legal aid offices with grant writing, newsletters, and data analysis, allowing staff to focus on direct client services.

Key Term: “Force Multiplier”

This term means something that multiplies the effect or efficiency of your work. Generative AI is often called a “force multiplier” for legal aid because it helps you do more with limited staff and funding.

6. Pro Bono Partnerships

Some tech companies and law firms donate AI tools or licenses to nonprofits. These partnerships aim to reduce the cost barrier and ensure advanced AI systems are not solely available to large, well-funded law firms.

Improving Court Accessibility with Generative AI

Court-Integrated Chatbots

Courts are embedding chatbots on their self-help websites. Litigants can get guidance 24/7 on filing forms or responding to a lawsuit. This is especially helpful for those representing themselves in small claims, family law, or eviction cases.

Online Dispute Resolution (ODR)

Some courts use online platforms for small claims or minor civil disputes. AI can facilitate negotiation by helping parties communicate or by identifying common ground. These systems aim to reduce court backlogs and resolve conflicts quickly.

Real-Time Language Translation

Generative AI that translates spoken words in real time could assist non-English speakers in court proceedings. Although still developing, these tools hold promise for reducing language barriers.

Self-Service Kiosks and Virtual Assistants

In many places, you can find court kiosks with an AI-driven touchscreen interface, useful for people who lack home internet. The system answers questions about filing fees, hearing schedules, and required documents.

Challenges, Risks, and Ethical Considerations

Generative AI brings hope for expanding access to justice. However, it also raises important concerns:

Accuracy and “Hallucinations”

AI sometimes produces incorrect or fabricated information. Lawyers must review all AI outputs carefully to ensure factual and legal correctness.Bias and Fairness

AI models can learn biases from the data they are trained on. If not checked, these biases could perpetuate unfair treatment, especially for marginalized communities.Confidentiality and Data Security

Lawyers are responsible for protecting client information. Using cloud-based AI tools requires caution, ensuring data is not exposed or misused.Unauthorized Practice of Law (UPL)

An AI chatbot that crosses from providing “legal information” into specific “legal advice” could be seen as unlicensed practice of law. Developers and lawyers must set boundaries and use disclaimers to prevent confusion.Transparency and Informed Consent

Users should know when they are interacting with an AI. Lawyers must also disclose if they used AI to draft filings.Digital Divide and Accessibility

Not everyone has internet or the necessary devices. AI-driven solutions must be accompanied by in-person or low-tech services to avoid leaving people behind.Cost and Sustainability

High-end AI tools can be expensive. Nonprofits may lack the budget to maintain them. Grants or philanthropic partnerships can help ensure these tools remain available to the public interest sector.Regulatory Framework and Evolving Bar Guidance

Bar associations and courts are still issuing opinions on AI usage. Lawyers must stay informed about emerging regulations on data privacy, client consent, and ethical obligations.

Practice Pointer: Bias Checks

Whenever introducing AI in your legal work, conduct periodic “bias checks.” For instance, if you notice that the AI frequently misses certain cultural references or patterns, you may need to make adjustments to ensure your work product is fair and balanced.

Maintaining Human-Centered Justice

The lawyer’s role as counselor, advocate, and ethical gatekeeper does not vanish with AI. On the contrary, attorneys must stay vigilant, reviewing AI output for mistakes, checking for potential bias, and ensuring confidentiality. A balanced approach, where technology amplifies human expertise, holds the greatest promise for delivering justice.

Callout: Human-Centered Justice

Always remember that while AI can automate and expedite, empathy and direct human guidance remain crucial in law. Technology can never override lawyers role as fiduciaries to their clients.

Case Studies: AI-Driven Access to Justice Initiatives

Below are some real-world examples of AI in action for pro bono and legal aid:

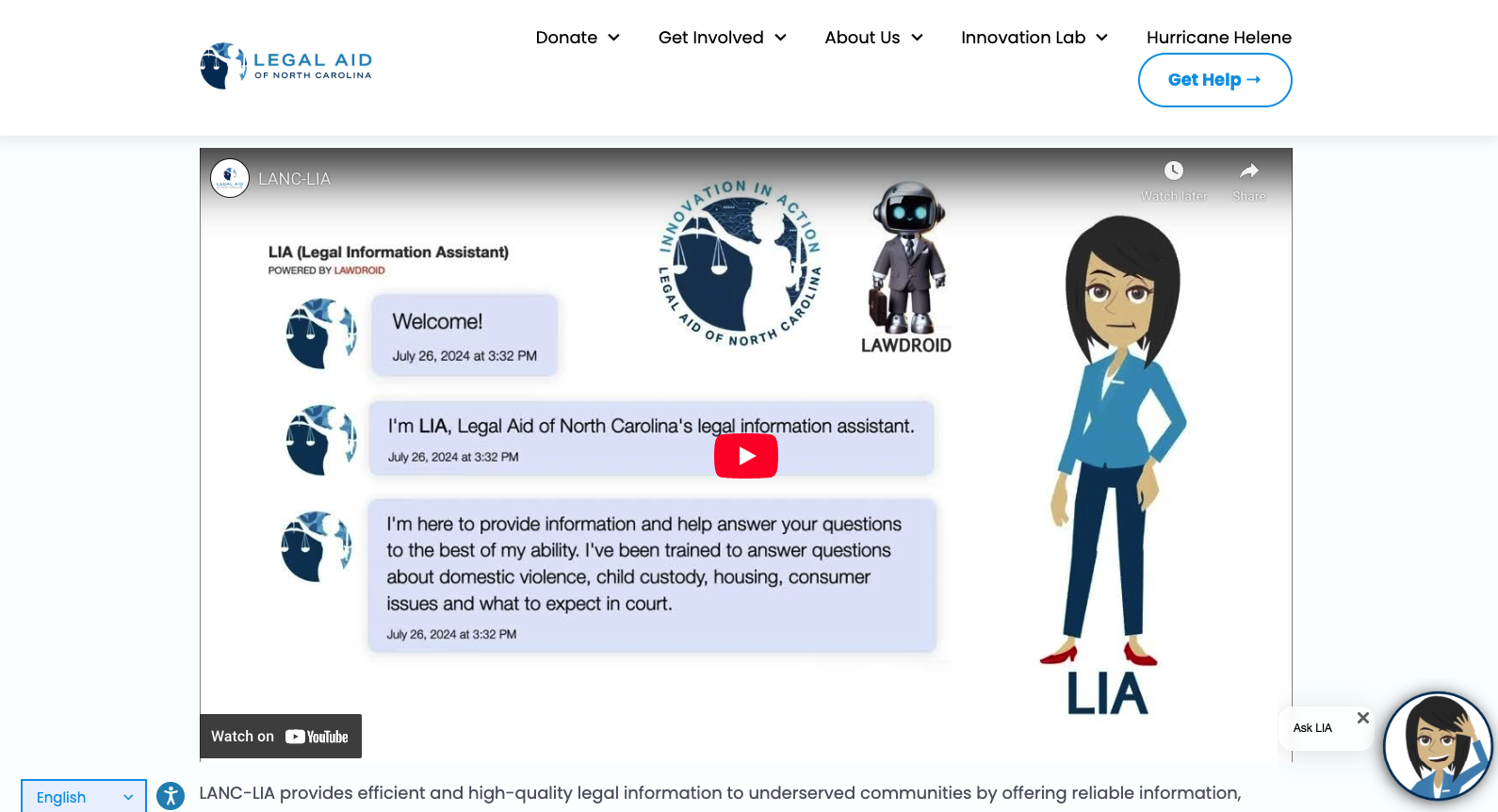

- Legal Aid of North Carolina’s LIA Chatbot

- What It Does: Offers multilingual legal information on housing, family law, and domestic violence.

- Impact: Thousands of users have received 24/7 assistance, freeing attorneys to focus on complex cases.

- Lesson: Carefully tested disclaimers and careful oversight are key to maintaining ethical standards.

- What It Does: Offers multilingual legal information on housing, family law, and domestic violence.

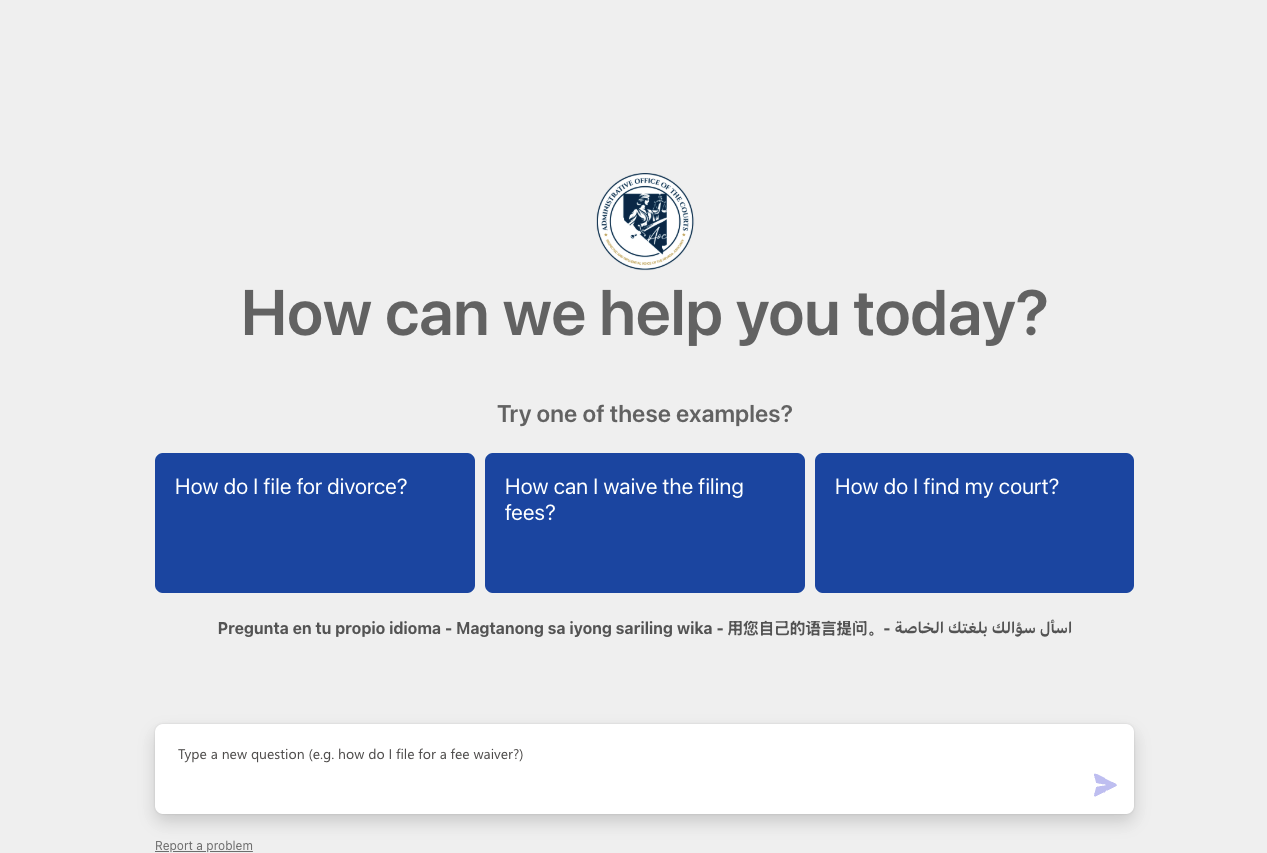

- State of Nevada Courts Self-Help AI

- Features: Interactive chatbot in 50+ languages, integrated with guided online interviews and e-filing.

- Reach: Deployed kiosks in libraries and courthouses for those without home internet.

- Outcome: Rapid adoption, hundreds of newly automated filings, and reduced staff burdens.

- Features: Interactive chatbot in 50+ languages, integrated with guided online interviews and e-filing.

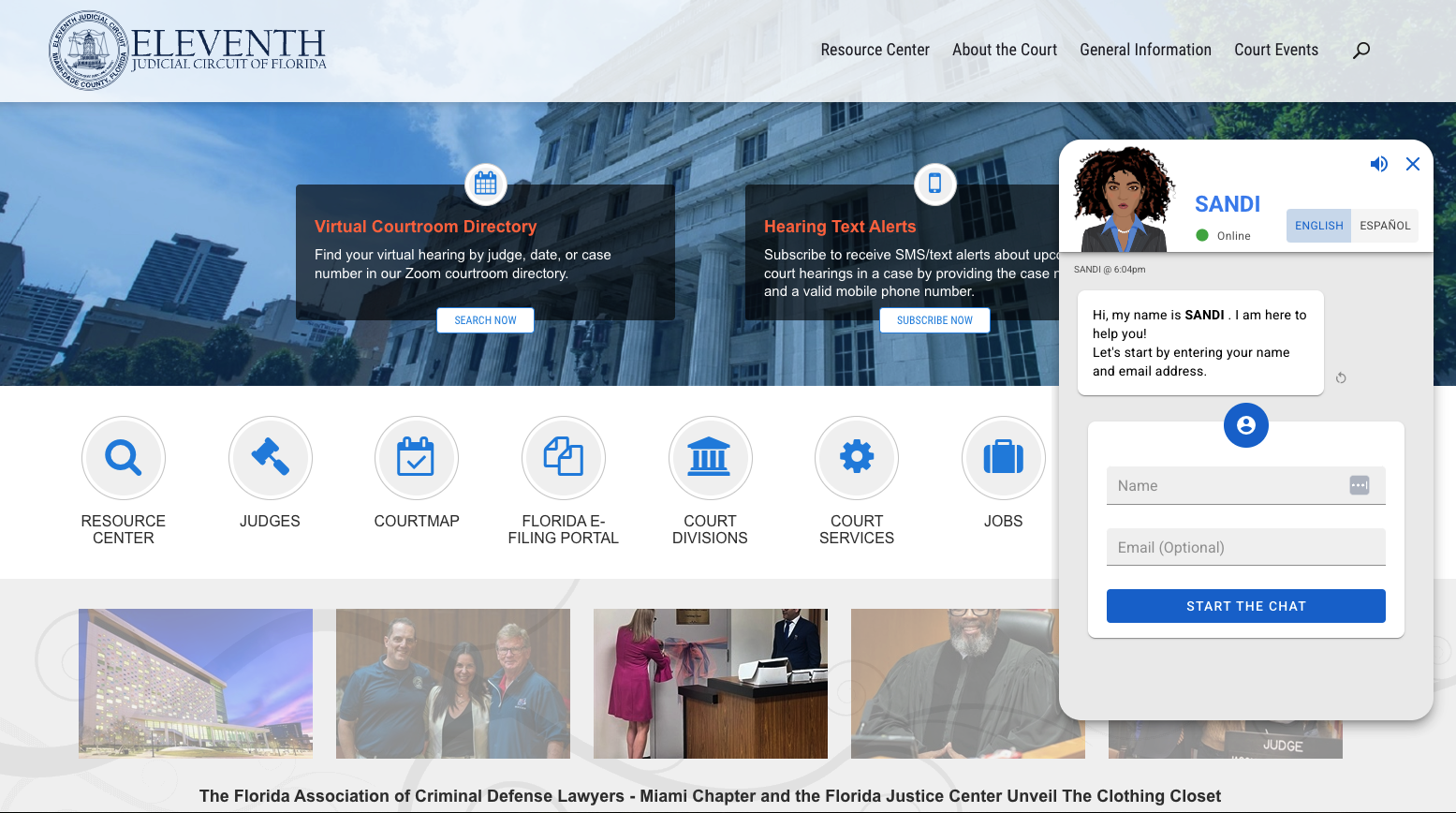

- Florida’s SANDI Court Navigator

- Role: A virtual clerk for self-represented litigants (pro se parties) in small claims and family law matters.

- Result: Fewer phone calls to the court, more prepared litigants.

- Takeaway: Even local courts with limited resources can implement AI effectively with the right planning.

- Role: A virtual clerk for self-represented litigants (pro se parties) in small claims and family law matters.

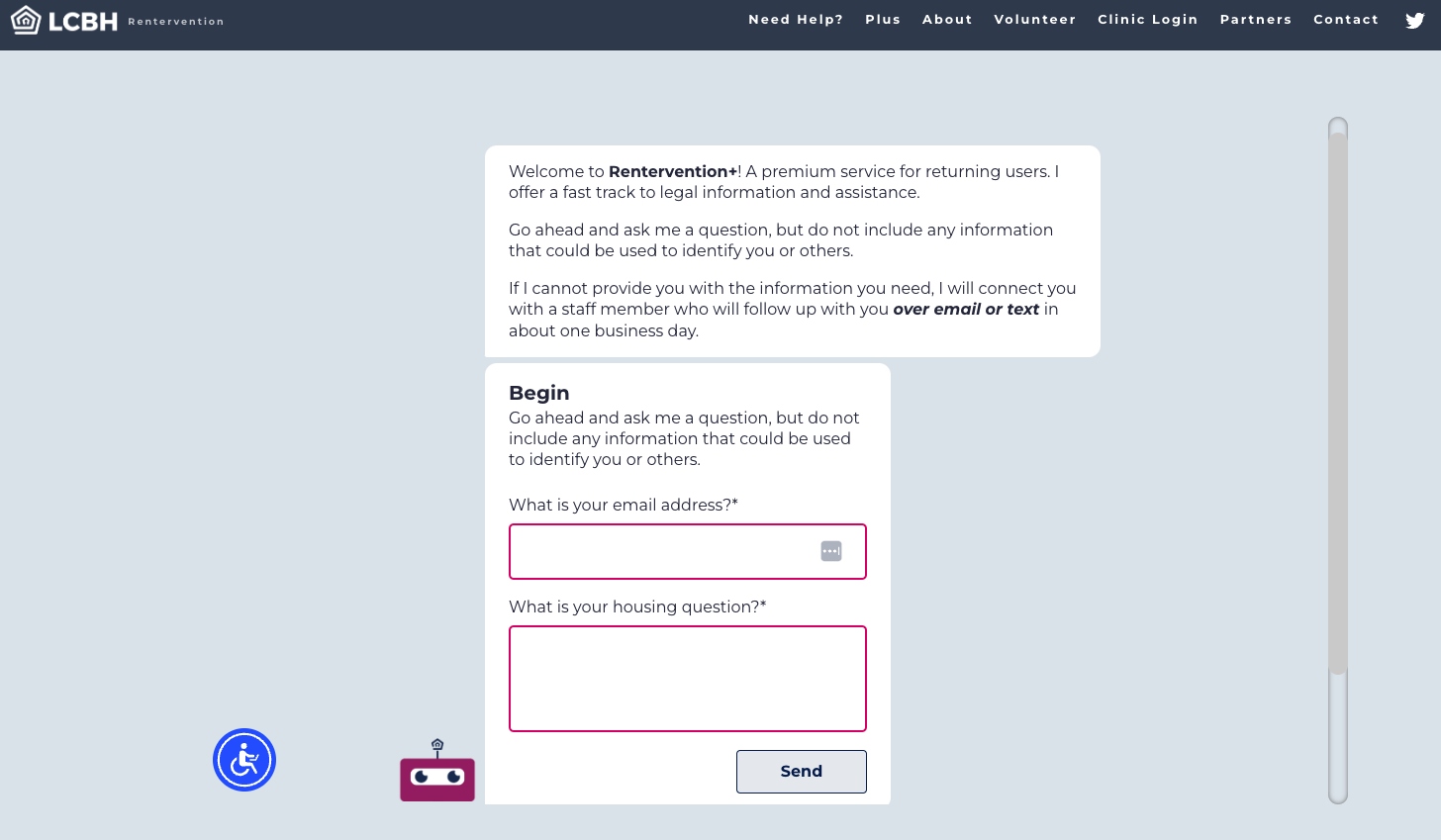

- Rentervention “Renny” in Chicago

- Focus: Tenant rights, drafting demand letters, and guiding eviction defenses.

- Benefit: Helps individuals address housing issues early, often avoiding formal eviction proceedings.

- Big Picture: An example of how specialized, issue-specific AI can empower communities.

- Focus: Tenant rights, drafting demand letters, and guiding eviction defenses.

Chapter Recap

In this chapter, we explored how generative AI tools can transform access to justice efforts and the delivery of pro bono services, particularly for low-income and marginalized communities. Major takeaways include:

The Current State of Access to Justice (2021–2023): Overburdened courts, underfunded legal aid, and public defender shortages continue to leave millions of Americans without adequate representation. Although the pandemic spurred remote hearings and new innovations, disparities by income, race, and geography persist.

Key Challenges in Traditional Models: Funding gaps, legal complexity, and the inability to serve everyone who qualifies for aid often translate into long waitlists and turn-aways. Rural “legal deserts” exacerbate these inequalities, and even well-organized pro bono programs cannot meet soaring demand for free legal help.

Generative AI as a ‘Force Multiplier’: Advanced chatbots, document automation tools, and AI-assisted research platforms can rapidly handle intake, draft pleadings, summarize case law, and even provide initial guidance to pro se litigants, thereby helping legal professionals focus on high-level advocacy.

Potential Future Impact: AI can increase efficiency and scale, reaching more people through online interfaces and enabling legal aid agencies to serve a greater number of clients with limited staff. Additionally, affordability is improved when routine tasks become automated, lowering overhead for nonprofits.

Ethical and Practical Considerations: AI “hallucinations,” bias in training data, confidentiality risks, and the need for human oversight require careful planning. Lawyers must remain vigilant about verifying AI outputs, complying with unauthorized practice of law rules, and addressing the digital divide so that technology benefits rather than excludes vulnerable populations.

Comparisons and Real-World Use Cases: From chatbots guiding tenants through eviction responses to AI platforms reviewing voluminous evidence for public defenders, practical initiatives across the country illustrate both the promise and the challenges of integrating AI into access to justice work.

With responsible implementation and a focus on user-friendly design, these tools have the potential to significantly narrow the justice gap, while preserving the vital human dimension of lawyering that technology can never fully replicate.

Final Thoughts

Technology alone cannot solve the deeply rooted inequities in our legal system, but generative AI offers a powerful catalyst for change. As the legal profession confronts chronic underfunding, overwhelming caseloads, and widespread underrepresentation, the combination of human insight and technological efficiency shows remarkable promise. Real-world successes, from AI-powered eviction defense chatbots to advanced analytics for discovery review, demonstrate how thoughtful implementation can help us reach more people faster and more affordably.

These tools demand vigilant stewardship to prevent amplifying existing problems. AI "hallucinations," biased training data, and confidentiality risks require consistent supervision and verification. The responsibility falls on legal professionals at all levels to ensure technology serves our ethical obligations rather than undermining them.

The most exciting prospect is how generative AI can help reduce the persistent justice gap when paired with our professional duty and compassion. By cultivating an approach that balances technological innovation with human connection, we can make "justice for all" more achievable. This path, while challenging, offers profound rewards for those committed to the ideals of our profession, scaling our impact while preserving the ethical foundation of meaningful justice.

What’s Next?

In Chapter 10, we’ll bring together the major themes and lessons from Chapters 6–9 in a comprehensive review session. This will give you a chance to reinforce key concepts about generative AI’s technical foundations, ethical obligations, and practical uses in the legal system. We’ll revisit the essential points from each chapter, ranging from prompt engineering, to the impact of AI on the business and practice of law, to ethics and the regulatory considerations that guide responsible deployment.

With the help of your textbook, chatbot tutor, podcast, and minilecture, you will have the structured, focused review you need to walk into the next multiple choice exam with confidence.

References

American Bar Association & National Center for State Courts (2023). Public Defender Caseload Standards and the Future of Indigent Defense.

Biron, C. (2024). Legal aid and AI help poor Americans close ‘justice gap’. Context by Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Chien, C. & Kim, M. (2025), Generative AI and Legal Aid: Results from a Field Study and 100 Use Cases to Bridge the Access to Justice Gap, 57 Loy. L.A. L. Rev. 903.

Legal Aid of North Carolina (2024). Press release: LANC launches AI-powered virtual assistant to enhance access to justice.

Legal Services Corporation (2022). The Justice Gap: The Unmet Civil Legal Needs of Low-Income Americans.

Pro Bono Institute (2024). AI Ethics in Law: Emerging Considerations for Pro Bono Work and Access to Justice.

Pew Charitable Trusts (2020). Debt Collection and the Transformation of State Courts.

Safdie, L. (2025). AI and legal aid: A generational opportunity for access to justice. Thomson Reuters Institute.

Washington Council of Lawyers (2024). Best Practices in Pro Bono: Using AI to Further Access to Justice.

ABA Journal (2025). Access to Justice 2.0: How AI-Powered Software Can Bridge the Gap.